RETURN OF THE PRODIGAL SON

BOGOLJUB BOBA JOVANOVIĆ

Notes from his life and work

In today’s Nemanjina Street, number 34,[3] he had a cottage built. Himself an eccentric, as his great-grandson tells, Jan was married to Katarina and had a son Bohumil and a daughter Božena.

Bohumil (1839-1924), Boba’s grandfather, was twelve years of age when his parents arrived in Belgrade. Having finished his schooling in Belgrade, Bohumil became an expert in statistics and the founder of modern statistics in this country. He worked as a statistician in the Ministry of Education and was director of the State Statistic Administration in Serbia. He wrote a number of works both in Serbian and German. A Catholic by his father’s faith, Bohumil converted to Orthodox religion and received a new name – Bogoljub – and a new surname – Jovanović, derived from Jan. With his wife Emilija[4], neé Dimić, a Serbian girl from Novi Sad, former professor of French in the high-school of Kragujevac, he had a daughter, Milica, and two sons, Dragoslav (1886-1939) and Branko. In 1906, in the vicinity of his father’s cottage he had a house built for his family, but larger.

Boba’s father, Dragoslav, graduated from the Faculty of Law in 1911 and was immediately elected Teaching Assistant.[5] His doctoral dissertation, which he defended in March 1923, was printed under the title “The Concept of Law in the Geca Kon Publishing House”. He was a university professor and one of the most progressive Rectors of Belgrade University (1936/37-1938/39). „I heard he was called ’the students’ guardian angel’. He used to protect many left oriented students and was a favourite professor.“[6]Let us add that Dragoslav did not only protect the so called „progressive“ students, but even those who belonged to the fascists of Dimitrije Ljotić. For him, each student was a student. There is still in Belgrade the street named after Dragoslav Jovanović.

In his marriage with Milica, a Serbian girl from Bijeljina, he had two sons and a daughter. The elder son, Bogoljub (1924), was named after his grandfather, the younger was Desimir, nicknamed Beka, and the daughter Emilija. For his family, he had a three-storey house built in 1927 within the complex of the previously built two houses. The family stayed in that house after the premature death of Boba’s father and Boba lives in it today.

„Father’s death[7] was not just a loss and a blow for the family“, Boba would say, „but also the end of an epoch – the Second World War was beginning.“[8]

„The loss of his father“, remarks his daughter[9], „at a young age was hard to deal with and influenced him in many ways, I can see a lot of that darkness, fear and nightmare in his painting. And then there is also the wonder, mystery and beauty that can be found. It’s a shame not all his works survived, and he has had other losses in his life, but that is the ephemeral nature of this world as well and in spite of or because of that, the artist shares that beauty.”

Reminiscences of the now rare remaining friends and contemporaries of our painter help us at least to complete parts of the mosaic of the complex and interesting life of the mysterious Bogoljub Jovanović. Mrs Branka Antić[10] writes the following in a letter sent from Paris[11]: “I think I met Boba Jovanović when we were eleven or twelve years of age, e.g. when we moved to the house in 36 Nemanjina Street as Boba’s first neighbours. He was a good friend of my late cousin Pera Petrović, brother of Saša Petrović[12]. We used to see each other very often.

I did not know his father, he had died before we became friends. His uncle was a strange man, always alone, a recluse, but he would greet us with respect whenever we met.[13]

Boba’s mother, Mrs Jovanović, was a friendly and cheerful woman and it was a pleasure to talk to her. When she was young, she had opened a bookshop with her friend from Bosnia who later married a friend of Boba’s father (Sima Marković) who took her with him to the Soviet Union. Boba’s father met his future wife in that bookshop.

Boba’s brother Beka[14], four years younger, was Saša’s best friend and the best man at Saša’s wedding. He seemed a well brought-up young man with quite normal behaviour.

In the summer we frequently went swimming in the Sava, the whole company together. Boba often took along his sister Mila[15], several years his junior.

Towards the end of the occupation, during the allied bombing of the country, his family left Belgrade and went to a village. Pera visited them and told us later that Boba simulated madness and insanity so that the Draža Mihailović’s chetniks would not draft him.

He was not sure what to study, art or technical science. Before he went to the Academy, his mother took his drawings to renowned painters to see if he was talented enough; their appraisal was most favourable.”

He chose painting, enrolled the Academy of Fine Arts in 1943 and graduated in 1949. His professors were Mihailo Petrov, Marko Čelebonović, Nedeljko Gvozdenović, Ivan Tabaković. During the studies he was very close to Aleksandar Jeremić Cibe, who was his friend in private life as well. Cibe’s great friend was Ivan Prvan[16]. When Boba and Cibe met at the Academy they found out they lived in the neighbourhood and frequently went to classes together. They used to walk to the Academy and played different tricks on the way. The two of them came from different social milieus but it did not prevent them from going together with a group of young men to the house of Bora Grujić, the painter and a great connoisseur of classical music. They listened to music there, made parties and talked a lot. Other visitors were Mileta and Krsta Andrejević, Nebojša Mitrić, Vasa[17] Mihić, Cibe. Mileta brought Boba along.

“As a young man”, wrote Mrs Antić, “he was of leftist orientation, but not nowadays. He adores everything American.”

“He liked to watch Russian films after the war to see what life was like there.” He took part in the voluntary labour activities in building the Šamac-Sarajevo railroad, went to monasteries on excursions organised by the Academy, and on his own to Skopje and the surrounding area. He stayed with some relatives there[18], climbed to Vodno, drew Nerezi and the surroundings. On his way to Nerezi he came upon a soldier who was guarding Tito’s villa and upon the swimming-pool where some children were swimming. Since he was very fond of water[19], he jumped into the pool and nearly died. He ran against some rods in the water. Having had his bath and spared his life, he arrived in the monastery. There were guards there as well, but he was allowed to draw and make watercolours, the very purpose of his adventure.

Several years after graduation Boba decided to go to Paris, in order to broaden his views. In 1953, he obtained a passport and left for Paris, at the same time as Cibe and arrived there when Bernard Buffet was a star. Bogoljub was not interested – he had left something like that in his own country. Petar Omčikus, Kosa Bokšan, Milorad Bata Mihailović and Ljubinka Jovanović Mihailović were already in Paris. Life there was neither easy nor simple. In order to live, painters used to take on various assignments. Nalard, also a painter, used to evaluate Serbian painters. Bogoljub did not like him although Nalard invited him to exhibit at one of the salons. Jovanović refused the offer believing that what he was doing was quite personal and did not interest anyone.

Weary of life in Paris, Cibe and Boba decided to move on. Cibe returned to Belgrade while Bogoljub, after marrying Jasmina[20] who had arrived from Belgrade soon after him, and after the birth of daughter Emilija[21], left for New York in 1960. Their other daughter, Elena[22] was soon born in America. According to his own report, he packed all his drawings into a big and heavy roll, carried it with some friends and threw it in the water, or on a meadow, he could not precisely remember. However, he did leave something with Bata Mihailović, the painter, in Meudon.

After arrival in America, the couple rented a one storey house on West 24th Street and lived there until 1970. They used one floor for living and on the other Bogoljub had his studio. The artist was free to do what he wanted. He told me[23] that he would mount a frame across a wall and stretched a big canvas over it, which he cut as needed. Sometimes he would paint first and then cut the canvas. He made frames for his paintings himself and that gave him much pleasure. When the family split, they left the rented house. Jasmina and the daughters first lived in a rented house in Manhattan, then bought a house in New Jersey where they lived until the end of her life.[24]

Jovanović told me he then bought a house above the 200th Dykman Street under very favourable conditions. In a letter[25] to his friend the painter, Cibe, Boba wrote in March 1971 that he had recently moved to “a new address[26] under the conditions I do not want to elaborate now, but will speak about that when we see each other”. The space he moved in was not adequate for big canvases. In order to continue painting, he began to work on papers of various dimensions, using wax and coloured ink[27]. When he decided to move to Belgrade and spend the better part of the year there, he gave the house to his former wife on the condition that she rented the upper floor and paid the credit. It was then agreed that Boba could stay in the fully equipped basement when he came to New York. Everything went well until it was decided that the house should be sold: Jovanović no longer had proper lodgings when he was in America. The painter stored about fifteen big paintings in Jasmina’s house in New Jersey, but when she died, their daughters sold the house and the paintings are lost from then on.

Although he preferred the East coast of the country, he had to go to California on his future visits to America, and stay with Prvan.

The various jobs he did in New York provided him with enough means to live, stay engaged in art and dedicate the rest of time to – playing chess. According to him, he first went to Central Park where chess was played at a particular spot when the weather was fine. In winter, chess was played in the neighbouring pavilion which was also a shelter for the homeless. When he could no longer stand that, Bogoljub discovered a space, a long room on 72nd Street whose owner was a certain Charley Hidalgo[28]. People used to come there to drink coffee and pass the time, play chess or cards. A casino was on the upper floor. On one occasion some people passed by, went up the stairs and left very quickly. It came out that they were former card players, armed with pistols and had come to pick up the money. Boba says it happened only once. When Charley, a chess grand master, died in 1982, the company moved to another place on the same street, also with a casino; the owner was a money-lender and asked for exorbitant interest.

Although he did not live with his daughters after the divorce, Bogoljub was a caring father but still his daughter Emilija writes the following: “In my view he has always been first an artist (an observer and chronicler of the human condition) and other things were secondary to that (father, husband, friend, employee, etc.). His work always inspired strong opinions from bezveza (sp?) to compelling. This dichotomy is very interesting”.[29]

“Boba was always an odd character”, wrote Mrs Antić[30], “he rarely opened, and Branka Petrović[31] told us recently that she was afraid to approach him when she was young. He changed only in his advanced age, became sociable, nice, open and accessible. It was much easier to be friends with him, he was pleasant, sociable and even he himself wanted to meet us”.

After his journeys to Paris and then New York, Bogoljub came to Belgrade for the first time in 1967. He felt somehow like a tourist in the town of his birth and wrote to his friend Cibe after returning to New York, then his permanent abode: “It was nice to be a tourist in a strange country where you know the language. This sensation was supported by the weather and my stay in your studio. I should have thanked you long ago, your studio meant a world to me. I never thought I would find in Beogr. such an idiotic situation that even Mrs Mica was living in my studio. I did not even see the room where I ‘had lived’ fourteen years ago. Belgrade had not changed at all.”[32]

Returning to the country almost every year and mostly in the summer, he stayed in Belgrade, but also thought of going to the seaside. In a letter to his friend Cibe[33] he wrote: “…I thought I would write earlier, but the circumstances prevented me and all the better for it because I did not have anything to tell you before. Now I know that I shall appear in Belgrade in mid-August – if not prevented by something else. If I had money I would go to Dubrovnik. I have been thinking these last years of going somewhere, to an island, to spend ten days there, in mediation and preparation of big works. But then, in the last moment, I would change my mind fearing that I would be bored or that I would arrive at a terrible beach and ruin the few days at the seaside. Dubrovnik therefore seems the best solution and I leave islands for later when I may have ‘more time’. Perhaps it will be now. Perhaps I shall stay for six months there when I come in August. It does not depend on me.”

Jovanović came even twice a year to see his mother and sister. When mother died in 1982 Boba decided two or three years later to move back to Belgrade definitely and take care of his sister Emilija and their possessions, parts of which he had to retrieve.

“When she was a young girl, Mila (Emilija) was quiet, shy, fragile, a romantic. She studied music, piano.”[34] She fell ill later and mother took care of her until Bogoljub returned to Belgrade. To the end of her life[35] “they lived together. She took care of the house, they entertained friends and he went on holidays with her. She began to play again as if her memory from the young age was intact”. She went to concerts and the opera because Boba liked music and had taken piano lessons in childhood. There is still a big concert piano in his flat.

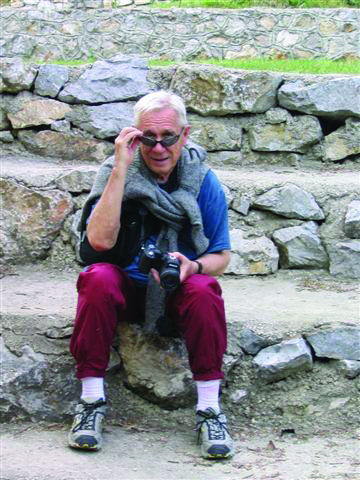

Although in advanced age, Bogoljub Jovanović goes to America almost every year. His last year’s trip in the early months of 2015 was in a way a journey into uncertainty. Although he responded to e-mail messages almost regularly there were moments without any news from him. Worried, I sent him an e-mail letter: “Dear Boba, not a word from you. It would be nice if you could write; we are eager to see you again in Belgrade. The book is progressing well and only you are missing. Kisses from Ivana.”[36] Then Bogoljub replied[37]: “Dear Ivana, you really know how to make one happy and needed. I have been much troubled with thoughts of the future lately (immediate, of course); future was infinitely uncertain, the present misty and puzzling and that was the reason I postponed my return to Belgrade. I have postponed it for May 6, the month of flowers, spring and the most beautiful promises. I am not easily embarrassed; they took my blood today, and I will soon be confronted with a CatScan and a vague future. Fortunately, future does not exist, the past has passed, there is only an evasive present which the vertiginous time is spilling from our hands and taking it away, flies like an arrow and fruit flies like a banana.”

He had an operation and returned to Belgrade recuperated; our meetings and conversations were continued. However, yet another e-mail arrived from America: “…Your questions strike where I do not want them to, I, a man who would like to squeeze through life like a dog through wet grass, to hide, not to show, now in my old age when there is only one little bit left to be endured – but, no, no way, there is Nemesis, Ivana, everything must come to light. There should be no secret under the sun. Signed: Evn Snowden. I have only now, after two months, seen the doctor, or he saw the X-rays I have brought with me and now he should make appointment for me for new ones, HIS scans and check-ups. It may happen that I stayed here even after mid-April. Keep in touch. Love. Boba”[38]

Today, we know Jovanović’s opus only in fragments. It is difficult to reconstruct completely what and how much he produced, although Bogoljub remembers a lot. What he had made in Paris has vanished[39] as well as many works made in New York.

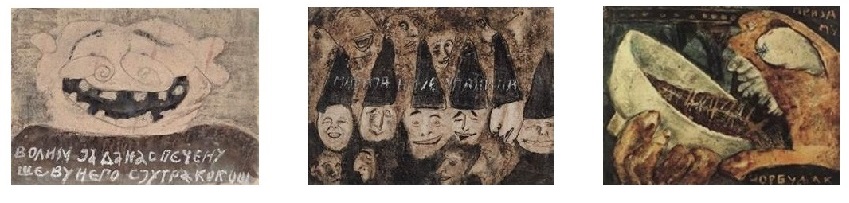

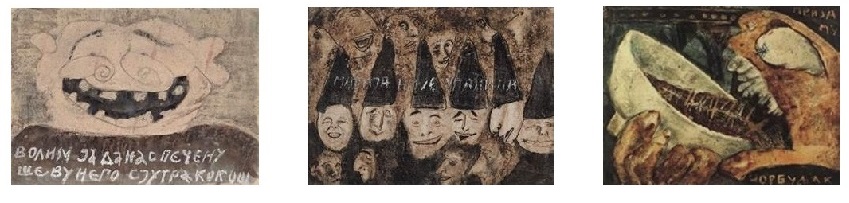

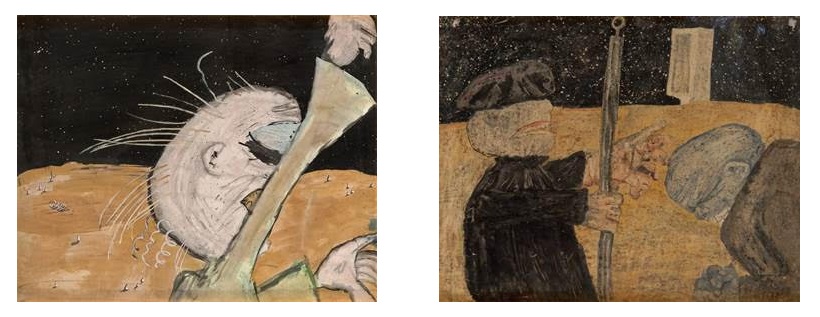

Between the 1970s and 1980s Jovanović was very prolific. As he says, he used to make very quickly numerous works in coloured ink and wax on paper. A smaller number of them he brought to Belgrade, much more were left in America. Although a whole series of those works called simply works on paper was first exhibited in Belgrade in the Gallery of the Association of Graphic Artists in 2006[40] I would call them works from the series SOMETHING PERSONAL because, as Jovanović says, there are frequent scenes from his own life and his own views[41].

He has brought something from America, but he also took something away from Belgrade. In one of his letters to Cibe, he wrote: “Before you leave, please go and see my mother and she will give you the black-and-white drawings, and drawings in pencil (there is only one, in fact – the house by the French Embassy, you will remember I drew it); they are on the piano and should be separated from the ‘magicians’. The Mag. should stay where they are. Those drawings are mostly illustrations for ‘The Twelve’ by Alexander Blok and I would like to have them here since I can easily reproduce them.”[42]

The illustrations for „The Twelve“ by Alexander Blok, displayed at Jovanović’s exhibition in 1953, and those he may have made in America have not been preserved; but his illustrations for Anatole France’s Thais, also exhibited in 1953, still exist. Anatole France is in a way Bogoljub’s obsession[43] and to the question wherefrom comes such partiality to this writer, he wrote from America: „Dear Ivana, my interest in and affinity for AF have roots in my youth and the liberation from the Stalin-Tito rule and Russian writers, several years later. AF – a SYNTHETIC DESCRIPTION OF HISTORY AND EVENTS was like a fresh breeze in the submarine of soc real and he fascinated me immediately. I shared those new post-communist ‘REVELATIONS’ with Vasa and maybe some others; FOR A LONG TIME WE WERE SEPARATED FROM THE WEST AND THE FREEDOM AND I CANNOT NOW LOOK BACK ON those ’atmospheres’ – I have forgotten a lot.“[44]

We know only fragments about what Jovanović was doing and how much he has achieved in life. In a letter to his friend Cibe[45] in which he mentions some films, he says: „I am writing a script to unmask Yugoslav music and toilets“ and suggests that he was „preparing to come to Belgrade again and get the feel of Belgrade winter. I miss that… I want to remember the old days.“[46]

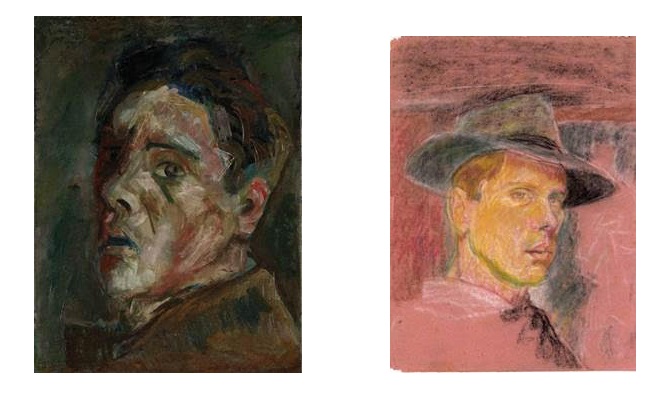

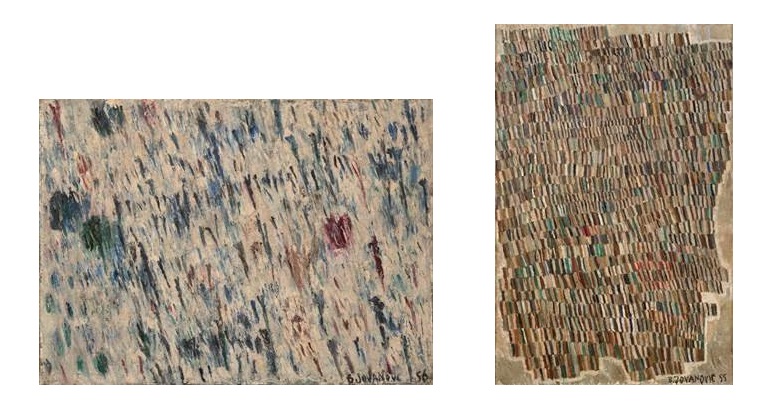

Only a few of his paintings (oils on canvas) have been found to this day: two abstract ones[47] and several portraits, but more of „small pictures on paper“ or „figurative gouaches and small format drawings“ from two cycles: the cycle of folk proverbs and the cycle of „Magicians”.

How much did he paint? It seems he drew even more. The preserved drawings[48] are numerous, made on small pieces of paper, frequently office paper. He used pencil, charcoal, pen (India ink, stain, ink), brush (washing, tempera) and wax in abundance in some works. He made numerous self-portraits (in pencil, charcoal, coloured), male and female[49] portraits of known and unknown personalities, nudes in most diverse positions, landscapes and veduttas, important buildings, free compositions, etc. Many drawings are dated, some have indications of the place of origin, but all of them are from the time before Bogoljub went to Paris. Only a few were brought from America.

January 2016 I.S.Ć.

[1] Boba still has a table in his flat carved by his great-grandfather.

[2] Today, the place is called Bohdaneč Lazni (meaning – spa). He was from the same place as the Kratohvil family. On one occasion, long ago, Bogoljub, as a great-grandson, visited the grave of the Smetivi family and noticed the grave of the Kratohvil family in immediate vicinity.

[3] At that time, it was a distant suburb of Belgrade, where „ducks used to swim“, as Bogoljub says.

[4] Boba’s sister will have the same name as will Boba’s elder daughter.

[5] He stayed in Belgrade until 1913 when he received the Marić Fund grant and continued his studies at the Faculty of Law in Paris. He returned to Belgrade after the beginning of the war and worked for the Pressbureau and the French Military Medical Mission. He remained in the country due to his illness and after the armistice he joined the Ministry of Finances as the head of the General Directorate of State Obligations.

[6] The words of Mrs. Branka Antić – see reference 10.

[7] He died on 16 August 1939.

[8] From the interview with Ljiljana Ćinkul, BOGOLJUB BOBA JOVANOVIĆ. WORKS ON PAPER, Gallery of the Association of Graphic Artists, Belgrade, 23 October – 11 November 2006.

[9] In search of more information about the life and work of the painter Bogoljub Jovanović, who is sparse but not forgetful in his reminiscences, I had to contact his daughters, although I had spoken to him on numerous occasions. The elder daughter, Emilija, kindly responded to the appeal and sent several mail messages with photographs of what she still had from her father in her possession, and also wrote about her memories of the days past. The above text is a quotation from Emiija’s mail.

[10] She lives in Paris and occasionally comes to Belgrade. During one of our meetings I asked her to remember the past and put on paper everything she knows.

[11] Dated 14 November 2014.

[12] Aleksandar Saša Petrović, a famous film director.

[13] The uncle was very strange according to his cousin as well. He never completed university studies although he studied with Jung in Geneva, and also architecture in Grenoble. He was an erudite and as Boba says „a walking encyclopaedia“. He worked as proof-reader in the State Print-house.

[14] His real neame was Desimir and he died in November 2015 in Cologne, where he lived.

[15] Real name Emilija.

[16] Ivan Prvan had almost no official education, but he was very clever. He was born in Dubrovnik, but came to Belgrade with his mother at an early age. He sold paintings and worked for some time for the Association of Serbian Artists. Afterwards he worked with theatre director Mira Trailović. He got a passport on account of her recommendation. When he arrived in Paris, he threw his passport away and brought her into a very unpleasant situation. After a certain time, his wife Olga also arrived in Paris and they both went to America where he worked as a watchmaker. When Olga died, he married Katarina and lived in California. Bogoljub was friends with Prvan and use to stay in his house when he went to America after he had finally re-settled in Belgrade. Prvan had many Jovanović’s paintings, but they were lost after Prvan had died.

[17] His real neame is Velizar. Since it was not an easy name to pronounce in America he was called Vasilije, shortened to Vasa. He also went first to Paris and then to America in 1960. He stayed in New York for a couple of months and then moved to Los Angeles, where he still lives. In the beginning life was difficult and he accepted various assignments, but in the coming years…

[18] It was in 1947 or 1948 Bogoljub remembers precisely. Some drawings made during those travels confirm the years.

[19] Even today, in his advanced age, he goes to Ada and to the swimming-pools as he did every time he came only to visit his friends in Belgrade. In a letter to Cibe of 17 July 1982 (hand-written in Cyrillic script) he wrote the following: I shall go to Belgrade most probably in early August. Please make sure that the weather at Ada… and that there are boiled corn cobs and tomatoes at the Klenić market… I have written to Prvan and thought of going there in late July but they are expecting guests at that time and may be going to the Lake Tahoe, so that I would probably stay here and go straight to Belgrade.

[20] An art history student.

[21] In January 1959.

[22] In November of 1960.

[23] Frequent meetings, conversations and correspondence (when Bogoljub was away in the USA for various reasons or in Germany visiting his brother and brother’s family) began in July 2014, from the mopment he won the „Stojan Ćelić, artist, theorist, critic, academician“ award established by the ZEPTER MUSEUM.

[24] She died in 1999.

[25] In mid-eighties, after getting permission from Bogoljub Jovanović, Aleksandar Saša Petrović and Stojan Ćelić decided to organise an exhibition for him in the Gallery of the Cultural Centre of Belgrade. On that occasion, Cibe gave Stojan Ćelić a number of letters and photographs Bogoljub had sent to him from America; in an accompanying letter he wrote: Stojan, there are many letters and other materials and I hate to throw that away, so I am sending all that to you to go through and see if you may need it. Do whatever you want, even throw them away, I can’t, Greetings AJ Cibe, 20 November 1986. However, Jovanović changed his mind and did not allow them to organise the exhibition and Ćelić did not make use of the offered material. The letters and photographs have been preseved in Ćelić’s legacy and some of them are being used on this occasion.

[26] 71, Payson Ave., New York, N.Y. 10034.

[27] Although some of the pictures he brought from America were dated 1962, 1963 on the back, in his own hand, there must be a mistake. Bogoljub is not able to remember exactly what had happened, but he maintains now that not one of them could have been made in the sixties and seventies since he began to paint like that only after he had moved from the big studio in which he worked on enormous canvases into the space where he was able to produce only smaller pictures.

[28] Spanish family.

[29] E-mail letter.

[30] Letter from Paris of 14 November 2014.

[31] The wife of Aleksandar Saša Petrović.

[32] A typed letter dated February ’68 – see reference 25.

[33] Handwritten and dated 11 July 1981 – see reference 25.

[34] The letter from Mrs. Branka Antić from Paris, 14 November 2014.

[35] She died in 1997.

[36] 7 April 2015.

[37] E-mail of 8 April 2015.

[38] E-mail of 6 March 2015.

[39] By pure chance the painting K-55, made in Paris, was exhibited at the Biennial in Rijeka in 1956. It remained in Rijeka until the 1980s when it was found and brought to Belgrade for the exhibition YUGOSLAV PAINTING OF THE FIFTIES, Yugoslav Twentieth Cenury Art, Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, July-September 1980.

[40] The exhibition of these works was organised by Ljiljana Ćinkul, BOGOLJUB BOBA JOVANOVIĆ. WORKS ON PAPER, Gallery of the Association of Graphic Artists, Belgrade, 23 October – 11 November, 2006. The works were then dated to the sixties and seventies but new assessment shows that they could not have been made then but a decade later – see reference 27.

[41] Arrow is a frequent motif in these works. On several occasions Jovanović said that the origins of the arrow were in the past and his youthful pranks. He remembers how they used to play William Tell, although boys of 16 or 17, in the courtyard of his house. They made arrows from broken umbrellas. One of them would put an apple on his head and the other would shoot the arrow. Once, while the apple was on Jovanović’s head, the arrow did not hit the apple but almost hit his eye (the cheek-bone under the eye).

[42] Handwritten letter dated, Sunday 22 August 1971.

[43] He still thinks of continuing his work on illustrations for thais (tranaslated into Serbian as Taida).

[44] E-mail of March 6, 2015. For Thais see the text by Ješa Denegri, p .

[45] Dated Sunday 14 November, 1976.

[46] Typed and dated 14 November 1976.

[47] One called K-55 from 1955, for decades kept in the Museum of Contemporary Art, although not in their ownership. That painting, as Jovanović wrote on 28 January 2015 „is still in my possession. They have used it for 50 years without my permission, just as they confiscated our property and built their house on it. They must pay me the rent“, and another one Untitled from 1956, found together with three portraits in recent reconstruction of Bogoljub’s former studio. After conservation and restoration, the author gave that painting as present to the ZEPTER MUSEUM and it was first shown at the exhibition BETWEEN THE PRIVATE AND PUBLIC, Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina, Novi Sad, May-June, and The House of Bequests, Belgrade, July 2015.

[48] Mostly with collectors particularly with Miloš Vujasinović, Ratko Simićević, Zvonimir Osečki and Toma Ljubisavljević.

[49] There are more male portraits, but there is a sufficient number of female ones, although on one occasion Bogoljub said he did not like to draw female portraits and made them only if commissioned.

ZEPTER MUSEUM

Knez Mihailova street 42,

11000 Belgrade, Serbia

+ 381 (0) 11/ 328 33 39

+ 381 (0) 11/ 33 00 120

ENTRANCE FEE

200 RSD, 100 RSD, free

Opening hours

- Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays

- 12 noon – 8 pm

- Saturdays, Sundays

10 am– 8 pm